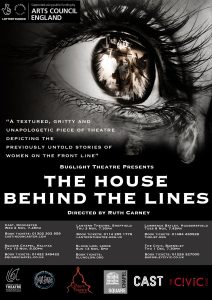

I am utterly delighted that after years of hard work ‘The House Behind the Lines’ will open to audiences in Yorkshire this Wednesday.

The play takes a look inside the brothels of the First World War, and gives a voice to the women who worked in them.

The play takes a look inside the brothels of the First World War, and gives a voice to the women who worked in them.

I feel very humbled that it has its origins in a piece I wrote for the Daily Mail on prostitution in the First World War.

Understanding this aspect of the First World War is immensely important. It gives us a more comprehensive understanding of life in the trenches. At least a significant minority of British soldiers indulged in visits to prostitutes. Brothels provided them with a refuge from the horrors of the trenches. They were urgently needed by younger men who did not want to die virgins. Others saw sexual activity as a necessary component of being part of a virile fighting force.

Knowing about this aspect of the Great War also guards against any tendency towards excessive sentimentalism.

When we think of soldiers going over the top, we imagine them waiting in fear for the whistle being blown. We don’t think of the very unidealistic way in which many men reacted to that prospect. They had sex with prostitutes.

But most important is the new narrative of the First World War that ‘The House Behind the Lines’ introduces.

In all the research I’ve carried out, I haven’t found a single account by a prostitute describing what she went through during the First World War, despite tens of thousands of women being employed in this way.

‘The House Behind the Lines’, and its use of drama, gives a voice to these women in a way historians can’t.

It puts ‘girls’ who served ‘so many customers’, as one soldier put it, that ‘they had to be sent home in cabs as by that time most… were unable to walk’ alongside other groups who we readily acknowledge as suffering in the First World War: the wounded soldier or the grieving parent.

The play also allows prostitutes to take their place alongside munitions workers or female auxiliaries, as groups of women who saw their employment and economic opportunities change with the war.

Turning the spotlight onto this aspect of the war also makes this play incredibly important for the present.

Sexual exploitation against women and children in wartime remains a formidable challenge.

If we prefer to overlook this aspect of a war that happened a hundred years ago is, what chance do we have of tackling it in the present?

For tour dates and tickets for ‘The House Behind the Lines’ visit Buglight Theatre.