Last night I witnessed the most harrowing, horrible, sickening footage I have ever seen.

Night Will Fall is a remarkably euphemistic title for a film that so unflinchingly portrays scenes from one of the worst episodes of human history: the Holocaust. It is currently being shown at the British Film Institute (BFI).

The footage upon which the film is based was taken at the time of the liberation of the Nazi-run concentration camps. 8,000 feet of film reel from eleven camps was recorded by ordinary soldiers, British, American and Russian. The chiefs of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force were so shocked by what they saw that they commissioned Sidney Bernstein of the Psychological Warfare Division, later founder of Granada Television, to turn the footage into a film.

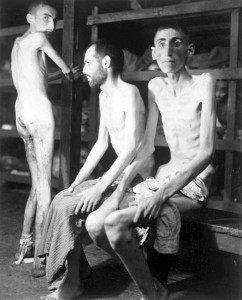

Two American soldiers conducting an investigation of a sub-camp of Buchenwald. They make notes while examining a corpse lying near a barbed wire fence.

The documentary was never shown. The film, with the aim of demonstrating to defeated Germans what had been done in their name, and the even more monumental aspiration of ensuring that such crimes against humanity would never be repeated again, was unceremoniously shelved. Whilst Bernstein and his team, which included Alfred Hitchcock, worked over the summer months of 1945 to produce a ‘systematic record’ of what had happened in those camps, the political situation rapidly changed. Rather than getting the Germans to accept responsibility for their own guilt, the Allies’ priority became the reconstruction of Germany. They needed the support of the Germans to do this. Building up Germany became particularly imperative with the deteriorating relations between the Soviet Union and the West.

Night Will Fall captures this story. It consists of the original footage shot in 1945, with a narrator speaking from the original script. There are interviews with the men who shot the footage, and the concentration camp survivors who feature in the original film. This is all framed within Helena Bonham Carter narrating the wider context of the making, and subsequent shelving, of the film.

I felt physically sick at what unfolded before my eyes.

Most powerful were the seemingly endless shots of emaciated, naked, dead bodies being gathered up following the camps’ liberation and thrown into mass graves by soldiers. It wasn’t so much their absolute emaciation. I have seen before images of dead and alive men and women, with protruding cheekbones, ribs and hips, sunken eye sockets and thighs ready to snap. This was different. Here were dead bodies being dragged, picked up, flung over a shoulder. Each body contorted as it was moved about; bones appeared and protruded under the flesh, in unrecognisable, gruesome ways. The corpse was then thrown amongst others, not gently laid down, there were too many for that, but all flung randomly together.

The nakedness was particularly horrible. Of course, it added to the indignity of these men and women: their indignity, we witnessed, continued into death. I felt almost complicit seeing them in these states. But even more horrible: the gentalia of the men, the pubic hair and breasts of these women, seemed to be the only things that made them recognisable. The parts of our bodies that culture requires us to cover up were the parts that identified them as human.

We saw bodies unburnt in the crematorium ovens, the camera zoomed in on a collection of hands and arms, almost grabbing out towards the door, towards the camera and towards us. There was a wide shot of survivors sitting on a large plain of grass, eating and drinking, but strewn around them were the dead bodies of their fellow inmates. How, I found myself asking, was it possible for someone alive to sit amongst that scene, what had they been through to make this situation tolerable?

A different form of death shown in the closing footage was equally hideous. The film ended with close ups of those who died from gunshot wounds, images normally reserved for clinical examination in medical textbooks. There were those with single bullets put through their brains, the holes so neat and delicate that they almost mocked the cruel circumstances of their death. Others had craters in their heads.

The film was also so powerful for what it was unable to convey. Time and again the interviewers and narrator referred to the smell of the camps, the original script was so desperate to make this point that the narrator drew upon two senses in order to convey the power of one. He spoke of how soldiers approaching the camps could ‘feel the smell’. It was also acutely obvious how the interviewees, particularly the soldiers who were involved in the liberation of the camps, lacked a language with which to describe what they had been through. ‘Hell’ and ‘horrible’ recurred again and again but, when matched with the images, these words were strikingly bland, mundane and superficial.

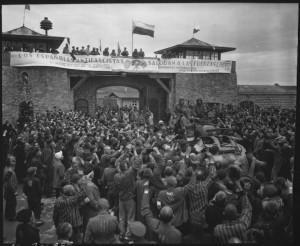

Liberated prisoners in Mauthausen concentration camp near Linz, Austria, welcome Cavalrymen of the 11th Armored Division.

That was another strength of the film: it reminded us that the concentration camps did not close with their liberation. The struggle of the veterans to describe their experience reminded me of articles I had read on G.I. liberators who tried to tell people at home of the camps, but their photos and descriptions were responded to with disbelief, disgust or silence. They were silenced as a result. The footage also showed what happened to those survivors who remained in camps. They did not wish to go back to their original countries and Britain and America would not take them in. We only think of inhabitants of concentration camps as people who were held there under pain of death. It is a sad indictment on the post-war democratic world that after the Second World War these people then voluntarily stayed in the concentration camps: they had nowhere else to go.

Alfred Hitchcock is reported to have said, sometime in the 1970s, ‘At the end of the war, I made a film to show the reality of the concentration camps, you know. Horrible. It was more horrible than any fantasy horror. Then nobody wanted to see it.’

This is the final cruelty. Not only did this happen, but the world then refused to acknowledge it.

The original film about the camps and the new documentary will be shown on British TV as part of the 70th anniversary of the ‘liberation’ of Europe. This year, I criticised the First World War commemorations for sanitising war too much, for too frequently turning four years of carnage into pretty photo opportunities of poppies and lights. I was asked at one lecture what I’d like to see instead. I said a commemoration that unflinchingly recognised the horribleness, the cruelty, the grotesqueness of war: that recognises what all human beings are capable of doing to one another, given certain circumstances. We should all watch this film next year, every single one of us. It will be more effective and more sobering than anything else could possibly be. We should watch it so we face up to what happened seventy years ago, so we look it straight in the eye. Then maybe, although it will be seventy years too late, we could say with some chance of success: ‘never again’.