I know that reviews should be written by people who can be objective about a performance, and by those who have some sort of theatrical grounding, and that I don’t qualify as either, but I haven’t been able to resist because…

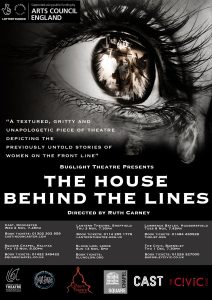

This week, I had the tremendous pleasure of seeing ‘The House Behind the Lines’, a play by Buglight Theatre on the hidden history of prostitutes on the Western Front in World War I. Buglight were inspired to make this piece of work after reading an article I wrote for the Daily Mail on the visits of soldiers to brothels in the First World War.

It was such a treat to see this untold story of the First World War brought to life on the stage, and it was so refreshing to see a play on the Great War where women took the lead parts. And these women weren’t the grieving mother, the waiting wife, or the munitions worker, whom we might more commonly associate with women in World War One, but they were two prostitutes and a brothel Madame. The two soldiers in the play were, quite firmly, in supporting roles.

The main plot focused upon Paulette and Chantal, who had been driven to prostitution in order to survive – one had no family and the other had children and a husband (who had been wounded in the war) to support – and their relationship with the exploitative Madame. I was a little unsure of this broad narrative. The focus on women exploiting other women possibly failed to instill a crucial point: prostitution was, and remains, one of the chief symbols of gender inequality.

There was much brilliance. I loved the set. Although the scenes took place in a brothel, the set was a trench. It meant the play was physically grounded in a First World War scene with which we are all familiar whilst dealing with an unknown aspect of the war. The way in which the scaling ladders became the beds on which the prostitutes lay was a stroke of genius. It both connected the prostitutes’ vulnerability to that of the soldiers going over the top to their death but it also meant that when the two prostitutes took their positions on these ladders, they resembled a crucifixion, so emphasising the sacrifice they were about to make of their bodies.

A recurring theme of the play, which I also really liked, was comparing the prostitute’s work to that of the soldier. This was particularly well done in a scene where a soldier getting his weapon ready for battle was interjected with a prostitute getting her body ready for an evening’s work. It made acutely clear the mechanical nature of these women’s work. This was also fantastically captured in another scene where Chantal and Paulette danced around the set whilst singing, with metronome rhythm, the repetitive cycle they went through evening after evening: ‘smile, laugh, wash, sex, pay, next’.

My background knowledge means I have glossed over the most important aspect of play. I knew that the British authorities sanctioned brothel visits, how hundreds of thousands of soldiers indulged in them, and that highly primitive measures were taken to avoid the spread of VD, but we rarely discuss these aspects of the First World War today. Instead it feels as we idolize and glorify the Tommy and his officer to an unhealthy and deluding degree. Through its narrative of sexual and economic exploitation, ‘The House Behind the Lines’ serves to give us a much more comprehensive understanding of what it meant to experience the First World War and brings to our attention the nature of sex work today.

My background knowledge means I have glossed over the most important aspect of play. I knew that the British authorities sanctioned brothel visits, how hundreds of thousands of soldiers indulged in them, and that highly primitive measures were taken to avoid the spread of VD, but we rarely discuss these aspects of the First World War today. Instead it feels as we idolize and glorify the Tommy and his officer to an unhealthy and deluding degree. Through its narrative of sexual and economic exploitation, ‘The House Behind the Lines’ serves to give us a much more comprehensive understanding of what it meant to experience the First World War and brings to our attention the nature of sex work today.