It is always exciting for me when a film or television series is released covering an area of history I work on. Suddenly, the rest of the world awakens to discover a subject that I’ve found fascinating and engrossing for years. And so it was that I went to see The Railway Man last night. It is based on the memoir of Eric Lomax who, as a POW held in the Far East, was tortured when guards found a radio he had helped to construct. The film switches from the period of captivity to the 1980s, when Lomax tries to come to terms with his experience.

Long gone are the days when I watch a period film for the insight it provides me with the past. I’m much more interested in analysing the narratives it draws upon to represent the past in the present, and I’m constantly thinking about what those narratives reveal about society today.

Three aspects of the film were particularly striking for me.

First, I thought it admirable and interesting and, perhaps, a reflection of the acceptance and prevalence of diagnoses of PTSD in our society that a central theme of the film was that war does not end with armistices or the signing of instruments of surrender: for individuals the experience continues to dominate their lives, physically as well as psychologically. Therefore, we see Lomax continuing to have nightmares about the torture to which he was subjected and his friend commit suicide, over forty years after the ordeal.

Second, I was very interested in how the film perpetuated the notion that Far East POWs were a ‘forgotten army’. Phrases such as Far East ex-POWs’ ‘code of silence’, ‘we do not talk about it because no one would believe it’, their experiences were ‘so bad, so humiliating, so shameful, I’m not sure you could ever talk about them’ were prevalent in the film. I’m just completing a couple of articles that contradict the idea that POWs were silenced, or did not talk about their experiences of captivity, after their return from the war. In fact, Far East ex-POWs ran a national campaign in the 1950s, now largely forgotten, for compensation for their treatment. This resulted in the experience of incarceration in the Far East receiving widespread attention in national and regional newspapers as well as in Parliament.

Finally, I found the end of the film most interesting. It focused on reconciliation, with Lomax writing to his captor ‘I have suffered much but I know you have suffered too.’ It reminded me of the ‘victimization discourse’, which emerged immediately after the end of the war in West Germany, which was used to displace feelings of guilt and responsibility. This ending also reflects today’s victim culture and the way in which narratives of suffering are the most dominant discourses now associated with the Second World War.

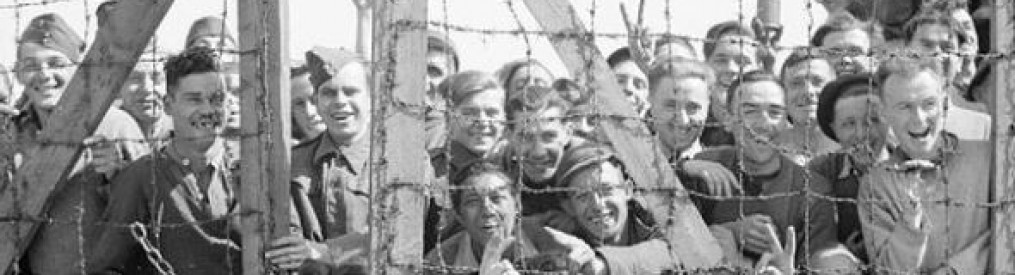

I’m also very interested to see what audiences make of such films. I think this is partly motivated by my desire to see how disconnected from the rest of the population academia has left me! When the film ended, I eagerly gathered my belongings and got up to leave, and then noticed I was surrounded by a solemn, seated silence. The film hadn’t moved me in the same way as the rest of the cinema. Yes, I found the scenes of torture appalling, but the film also failed to capture much of what I think was horrific about this period of incarceration: the starvation, illnesses such as dysentery, or legs torn open by tropical ulcers. In fact, I was shocked when I saw how healthy the actors looked. I am so used to seeing emaciated POWs in photographs or drawings that to see the death railway workers looking physically strong was actually a relief.